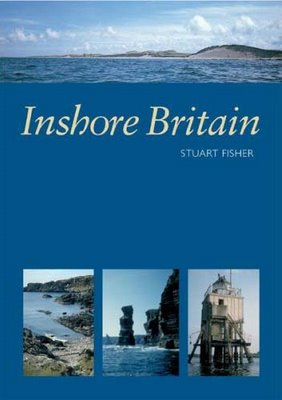

Inshore Britain provides nearly all the information you need to plan your paddle round the coast of mainland Britain but it is much more. It is packed with details of history, geology, wild life and lots of other things to look out for on the way.

I seldom buy books unseen but I did so in this case because Stuart Fisher has already published a series of articles about his voyage round Britain in Canoeist magazine. Many years ago I found a dog eared copy of Canoeist magazine, issue 123, in a second hand bookshop. It contained Stuart's article on paddling the Solway coastline. It was one of the reasons I took up sea kayaking and it also inspired me to write about it. I have since published two articles about paddling the Solway coast in Paddles magazine.

Inshore Britain arrived by post this morning. I was not disappointed. Published by Imray of Charts and Pilots fame, it is an A4 format and has 357 pages. On the back cover I was delighted to see a photo of a little known, but striking, rock arch on the Solway. Clearly Stuart has taken the time to paddle the coast and not gone from headland to headland as many circumnavigators have done to save time. It took him 15 years to complete his paddle round Britain. This is an author who has savoured his trips and his writing conveys his enjoyment and enthusiasm for exploring the coast by sea kayak.

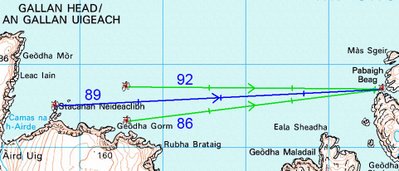

The book is divided into 62 sections starting with west Cornwall and working clockwise round the coast. Each section consists of 4 to 8 pages and covers a distance varying from about 80 to 180km. The section of coast is outlined by very clear but large scale line maps (you will still need other more detailed maps or charts). There are very many of the authors own photographs. They include a number of really excellent A3 wide panoramas but most photographs are quite small, given the format of the book. There is a highlighted text box covering local information including tidal constants. Tidal flows are mentioned in the body of the text and as some sections are nearly 4,00o words long, it can take a moment or two to track them down.

Taking the Solway section as an example, it covers 131 km in 6 pages. The line map covers the central part of two adjacent A4 pages and the text has been overlaid on the inland areas. There are 11 photographs that include close range shots of distinctive buildings and rock features but I also like the wide angle shots of distinctive hills and islands which give a good idea of the look of the coast from a kayak. The text is about 3,500 words. It is very well written and gives a detailed account of things to see not just from the kayak but covers points of interest a short distance inland as well. Stuart gives a good account of the weather conditions he met: "into Wigtown Bay where southerly winds rise with little warning and bring heavy seas". This is something I know of very well! However, for one person to have local knowledge of all the differing conditions of the whole coast of Britain would be expecting too much. He does not mention the strong gusty NW winds which come down off the Galloway hills and have caused many recreational boating fatalities over the last years. Nor does he mention the seasonal inshore lifeboat stationed at Mossyard as a result of these accidents (after Stuart had published this section in Canoeist) but he does detail the all year inshore lifeboat at Kirkcudbright. From my local knowledge of this section it is clear to me that Stuart has thouroughly paddled and researched the area. The guide would thus be invaluable to anyone new to the area who might otherwise miss a great deal. He has resisted the temptation to detail what is round every corner and there will still be the satisfaction of exploring and finding the unexpected.

A reviewer has to try and identify any weakness in a book. Well that would be difficult in this case. I have checked the Solway tidal data and it is accurate. Several of the caravan and campsites mentioned are no longer open to non resident visitors. The most kayak friendly campsite, Brighouse Bay, is called Pennymuir in the book, a name even the locals no longer use and a name which is not on the OS map. There are one or two typos including a page number on the contents page, so as usual, I would always use more than one source to check tidal data. A couple of others I showed the book to this evening thought there was too much text and the photos should have been bigger. Some of the older members of the sea kayaking club felt that his original magazine articles were a bit wordy. I disagree, I loved the few original articles I had read. Now they are gathered together in a reference book, I am looking forward to a number of long winter evenings engrossed, reading about new areas. Do note that the title is "Inshore Britain". It does not detail islands such as the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, Isle of Man, Arran, Mull, Skye or the Outer Hebrides.

This book is essential reference for any sea kayaker. It will allow you to get enough backround information to help plan a paddle in a new area (without buying all the local pilots) and also give you a wealth of background knowledge of the coast. Highly recommended.

PS A delightful touch is the use of postage stamps as small fillers throughout the book. These either have a nautical theme or have local relevance, e.g. a stamp of the Queen Mother's 90 birthday is situated near her summer residence on the map of the Caithness coast.