Most sea kayak navigation is done by identifying coastal features, checking on the map where you are in relation to them then paddling towards the one you want to get to. However, fog, night or tide might make things more difficult. I used to be a Luddite when it came to GPS units and it is fair to say that although I am a technophile, I was a late GPS adopter.

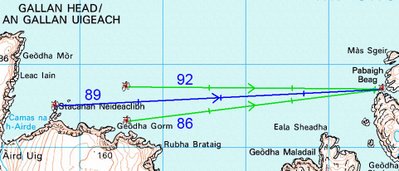

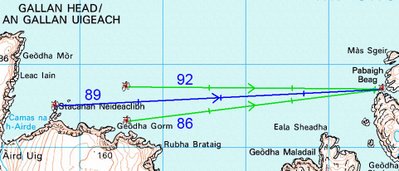

In this case I want to paddle to the channel to the south of Pabbay Beag from Stacanan Neideaclibh. The horizon is pretty featureless so I can take a grid bearing off the map, convert it to a magnetic bearing and the course is 89 degrees between the two points. I now paddle on a heading of 89 degrees and I should get there. But if there is a tide carrying me north from the course line, my bearing to my destination will change to say 92 degrees. I will have no way of knowing this unless I have calculated the speed and direction of the current before hand or if I have identified a more distant landmark behind my destination and the two move relative to one another (this is called using a transit). In this case there is no suitable transit landmarks.

In this case I want to paddle to the channel to the south of Pabbay Beag from Stacanan Neideaclibh. The horizon is pretty featureless so I can take a grid bearing off the map, convert it to a magnetic bearing and the course is 89 degrees between the two points. I now paddle on a heading of 89 degrees and I should get there. But if there is a tide carrying me north from the course line, my bearing to my destination will change to say 92 degrees. I will have no way of knowing this unless I have calculated the speed and direction of the current before hand or if I have identified a more distant landmark behind my destination and the two move relative to one another (this is called using a transit). In this case there is no suitable transit landmarks.

This is where a GPS comes in. I set a waypoint in its memory for the place I want to get to by either; 1. entering a grid reference, 2. on a mapping GPS scrolling the pointer to the map position then pressing the MARK key or 3. if I was there earlier in the day, by pressing the MARK key when I was in the middle of the channel.

Next I press the FIND key and select the waypoint. The GPS then calculates the distance and course from your start location. Most GPS units have a GOTO page which displays a large arrow which points on a compass rose to the bearing from your current location to your destination. If you drift off course then the bearing changes. On simple GPS units the bearing pointer points to the top of the screen if you are on course. On more sophisticated units the bearing pointer will point to the destination if it is held flat. This is all pretty complicated to describe and in practice in rough water and if your eyesight is not very good, you will end up a long way off course before you detect the change in the bearing arrow.

In practice it is easier to monitor any change in the bearing as a number. On my Garmin GPSMap76cs I can set the bearing to the destination on a large type screen as a number. This is very easy to see especially for those elder paddlers whose close up vision is no longer what it was. If the tide carries me off course to the north, the bearing might Increase to 92 degrees. I now paddle more to the rIght and the bearing comes back to the course of 89 degrees. If I was carried off course to the south, the bearing might dEcrease to 86 degrees. I now paddle more to the lEft and the bearing comes back to the course of 89 degrees. In practice it is easy to keep within about one degree of the course on typical sea kayaking distances.

The GPS allows you to maintain a perfect ferry angle despite changing tidal flows. This is a function that map, compass, tide tables, chart and your brain would be unable to match. Off course it needs to be used sensibly. If you are crossing a channel and expect to be half way across at the turn of the tide, you may as well paddle straight across on a constant bearing and allow yourself to be carried down tide then up tide and these will cancel each other out and you will not waste time ferrying into the tide. Another point is that GPS units can be set to use various Norths such as grid and magnetic. I always set mine to magnetic so that if the GPS fails I can just switch straight back to the compass.

I explained all this to a friend who is very keen on skin on frame kayaks and Greenland paddles. He was rather dismissive of all this technology and wondered what was wrong with a good old compass. However, I am pretty sure the Inuit did not have compasses (not to mention aluminium frames and polymer skins).

PS in response to Cailean's reply.

In May I was fortunate enough to be part of a group that was led out to the Ecrehouse reef which lies 10 km off Jersey in the path of tidal currents that run up to 5 knots.

The leader was a very experienced local paddler who had been out to the reef countless times. He used local knowledge, his experience, compass, map, tide tables and tidal flow charts to take us out by the southerly route above. It was a safe crossing and allowed us to get carried down onto the Ecrehouse. If we had missed it we would have ended up going to England. However, we battled for 2 km more than we had to into a 3.5-5 knot current which was extremely tiring and a couple of paddlers in the group were very nearly exhausted by the crossing. The leader knew I had a GPS and asked how we were doing at the point we changed direction.

If we had done this crossing using the GPS then I would have set a waypoint about 1 km up tide of the Ecrehouse (at our final change of direction on the chart above) and we would have paddled straight to it.

I do think that being able to ferry at just the right angle using a GPS can conserve a groups' energy to leave a reserve for any unexpected tide or wind conditions they might meet later.

Here is a GPS track of a trip to Ghigha. On the way out it was flat calm and slack water. On the way back there was a 2 knot north flowing tide and a force 6 southerly wind. I used the GPS track not to navigate such a short crossing but to adjust the ferry angle. As you can see it was an efficient crossing in somewhat lively conditions!