This was 19:03 on 11th May 2006.

We had just successfully executed a remarkable

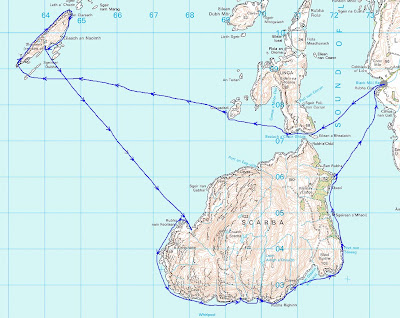

sea kayaking day trip from Glasgow. The night before, I had noticed (as you do) that the tides were right for a trip out through the Grey Dogs to the Garvellachs then back to Scarba, round its south end, through the Corryvreckan and back up the Sound of Luing. The snag was that Mike and I were working the next day and David was meeting an ex vet student friend from South Africa for their 40th year reunion dinner. Her flight got into Glasgow airport at 21:30pm that night. The only way to do this was to drive from the mainland over the Bridge over the Atlantic, onto the Isle of Seil then take the ferry across the Cuan Sound onto Luing and drive to

Black Mill Bay and launch there. A quick Google search for the ferry timetable brought up the Calmac website which showed regular sailings into the late evening.

We had aimed to get the 19:35 ferry and I was just congratulating myself on having half an hour to spare when an awful fact gradually invaded the euphoria of an amazing day. If you look closely at the photo above you will note that there is no ferry!

On our drive to the jetty I had noticed something that looked very like a ferry moored in a bay 1.5km to the south. Somehow I had managed to blot this unwelcome observation from my consciousness. Any sea kayaker that can work the tides through the Dogs and the Corry must be able to read a simple ferry timetable! I dug the Calmac printout out of my map case and we should have had another 3 ferries to choose from right up till 22:05. Something was not right and I soon found out it was when I walked over to the small waiting room. The Cuan Ferry is run by Argyll and Bute council and on their timetable (which was nailed to the wall) it was quite clear that the last boat ran at 1805.

David took it very well. Not only had I bashed his car getting off the ferry that morning, now I had got us marooned on Luing for the night and his friend would be stuck at the airport. A more highly strung party would have started arguing and shouting but not us. In the absence of a nearby sea kayaking hostelry, we cracked open three cans of Guinness from our emergency rations. Sitting on a grassy knoll in the spring evening sunshine, we pondered our options. First we found that our mobiles had no reception. Then we wondered if David should paddle across and try and hire a taxi to take him to the airport.

Then suitably refreshed, I decided to check out the waiting room. I noticed a small yellow notice.

"In case of medical emergency, call this number."

Well I'm a doctor. And it was an emergency! So I phoned it from the coin box phone outside. It turned out to be a call centre in Liverpool and the girl knew nothing about Luing or where it was. I asked her for the ferryman's number but she said

"I can't do that but I'll get him to ring you back."I looked at the ancient rotating dial phone. There was no number.

"There must be a number." she said.

David cracked open another Guinness to assist in the search for the elusive digits but there were none to be found. Then the girl had a brainwave:

"Give me your mobile number...""There is no point", I said, "none of our three mobiles are getting a signal."

I could sense I was stretching her incredulity. This city girl had probably never been out of cell phone range since she had been born. Indeed, her developing brain may have been partly modelled by mobile microwaves.

Then I had a brainwave:

"Just tell him to phone the Luing call box"

"What's the point of that? He wont know the number, there must be thousands of call boxes on Luing.""You don't know Luing! Please, just ask him to ring the call box, I am sure he will know the number."

About 5 minutes later the phone rang, it was the ferryman. I explained our situation and he agreed to come but he said he would need to call his mate who lived some distance away. He would then need to use a dinghy to get down to the ferry and fetch it back up to Seil, pick up his mate then come across and pick us up. (Then he would need to repeat the process to get the ferry back to the mooring.)

MV Grey Dog

We were ever so pleased as when he arrived. He knew all about the mistake in the Calmac timetable and said there would be no charge for the crossing. We had already resigned ourselves to finding bed and breakfast accommodation on Luing, which would have cost us about £20 each so we gave them £60 for their trouble. They were very reluctant to accept it but we insisted. They were obviously prepared (and pleased) to be able to help, for only a thank you in return.

Fortunately the 105 miles on the road to the airport were quiet and we pulled into the airport pickup area just as David's friend was exiting the arrivals hall.

What timing, it's amazing what you can cram into a day!